DNS Deep Dive

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Domain Name System (DNS) — the backbone of the internet. We’ll cover its purpose, architecture, record types, caching strategies, security mechanisms, and modern trends. Along the way, we’ll add real-world outages, interview tips, and troubleshooting practices, making this guide both practical and FAANG-interview ready.

Why DNS Matters

DNS is often called the “phonebook of the internet”, but for engineers it’s much more:

- Reliability: If DNS fails, your service is invisible, no matter how healthy your backend is.

- Performance: Optimized DNS resolution reduces latency globally.

- Scalability: DNS powers load balancing and geo-distribution of services.

- Security: Attackers frequently target DNS through spoofing or DDoS.

- Interview Angle: FAANG interviews often test whether you can design highly available, fault-tolerant DNS-based systems.

What is DNS?

The Domain Name System (DNS) translates human-friendly names (e.g., www.example.com) into IP addresses (e.g., 192.0.2.1). Without DNS, we’d be forced to memorize numerical IPs.

Core Functions

- Name Resolution: Map names to IPv4/IPv6 addresses.

- Service Discovery: Records for mail (MX), authentication (TXT), or services (SRV).

- Load Balancing: Direct users across multiple IPs.

- Scalability: Operates as a distributed, hierarchical system serving billions of queries daily.

How DNS Works

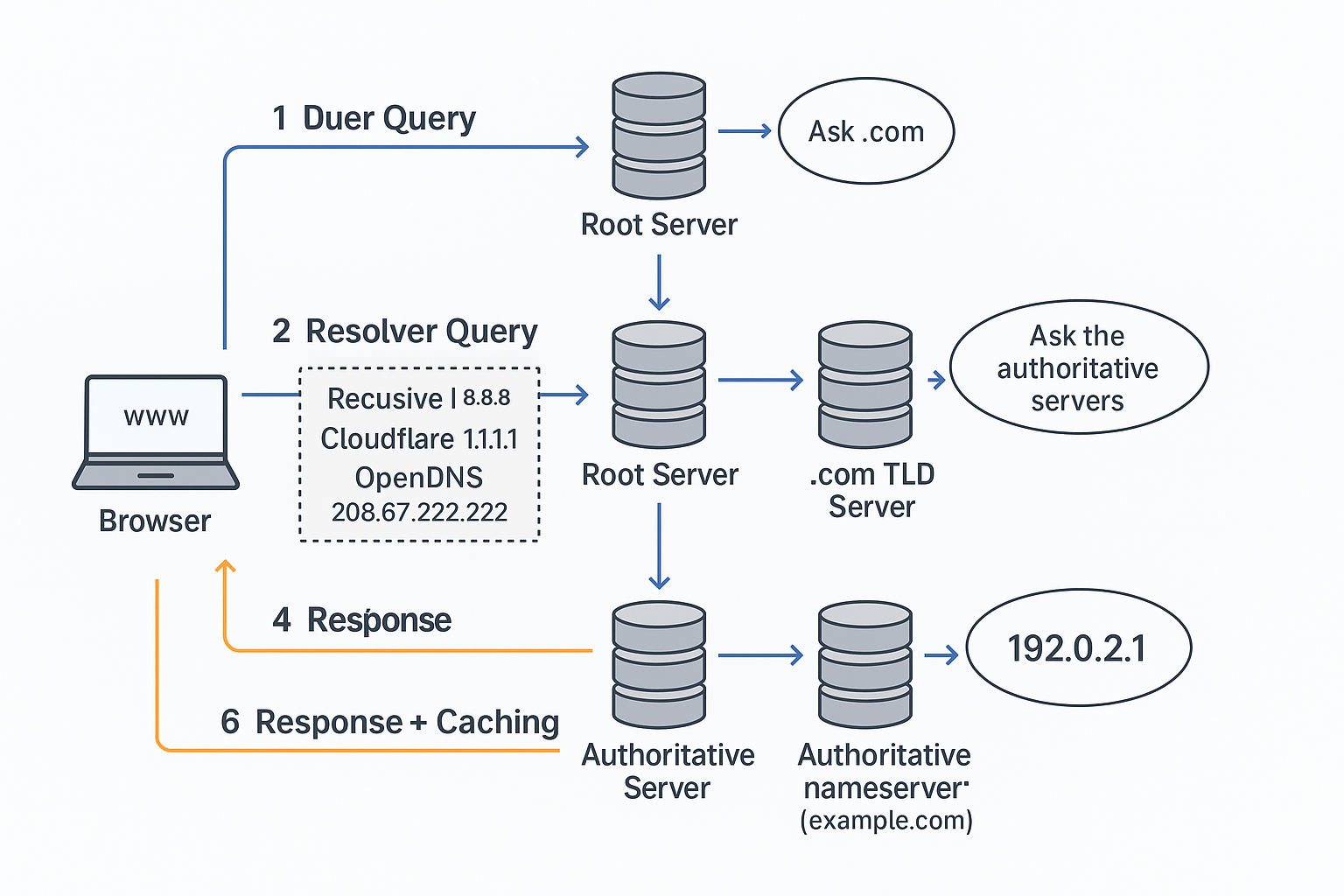

DNS Resolution Flow (Detailed)

The process of resolving a domain name into an IP address involves multiple steps across the DNS hierarchy. Here’s a breakdown with real examples:

User Query (Local Cache Check)

- The user types

www.example.cominto a browser. - The browser and operating system first check their local DNS cache.

- Example: If you recently visited

www.example.com, the IP may already be cached with its TTL (Time To Live).

- The user types

Resolver Query (Recursive Resolver)

- If not cached locally, the request goes to a recursive resolver.

- Common resolvers:

- Google DNS:

8.8.8.8 - Cloudflare:

1.1.1.1 - OpenDNS:

208.67.222.222

- Google DNS:

- These resolvers are responsible for doing all further lookups on behalf of the client.

Root Servers

- If the resolver doesn’t have the IP cached, it queries a root nameserver.

- There are 13 sets of root servers worldwide (labeled A–M), operated by organizations like Verisign, ICANN, and universities.

- Example:

- Root server

a.root-servers.net(IP:198.41.0.4) responds with: “Ask a.comTLD server.”

- Root server

TLD Servers (Top-Level Domain)

- The resolver then contacts a TLD server responsible for the domain extension.

- For

.com, TLD servers are operated by Verisign. - Example:

a.gtld-servers.net(IP:192.5.6.30) responds with: “Ask the authoritative server forexample.com.”

Authoritative Nameservers

- Finally, the resolver queries the authoritative nameserver for the specific domain.

- Example: For

example.com, the authoritative nameservers (as per ICANN) are:a.iana-servers.net(199.43.135.53)b.iana-servers.net(199.43.133.53)

- These servers store the actual DNS records (A, AAAA, MX, etc.).

- Response: “

www.example.com→192.0.2.1.”

Response + Caching

- The recursive resolver returns the IP (

192.0.2.1) to the user’s browser. - Both the resolver and the local system cache the result, obeying the TTL (e.g., 300 seconds).

- Subsequent queries for

www.example.comwill be faster until TTL expires.

- The recursive resolver returns the IP (

Full Example Flow for www.example.com

Browser → Local cache → Google 8.8.8.8 → Root (a.root-servers.net) → .com TLD (a.gtld-servers.net) → Authoritative (a.iana-servers.net) → Returns 192.0.2.1

DNS Components

- DNS Resolver: Handles recursive queries (e.g., Google Public DNS).

- Root Servers: 13 logical root servers (A–M) distributed globally via anycast.

- TLD Nameservers:

.com,.org,.uk, etc. - Authoritative Servers: Store domain records (e.g., AWS Route 53, GoDaddy).

- DNS Records: Entries like A, AAAA, MX, TXT that define mappings.

Types of DNS Records

- A: IPv4 address mapping.

- AAAA: IPv6 address mapping.

- CNAME: Alias (e.g.,

blog.example.com→www.example.com). - MX: Mail server.

- TXT: Arbitrary text (SPF, DKIM, domain verification).

- NS: Authoritative nameservers.

- SRV: Services + ports (common in VoIP, Kubernetes).

- PTR: Reverse lookup (IP → domain).

DNS Query Types

- Recursive Query: Resolver does the full resolution process.

- Iterative Query: Resolver follows referrals step by step.

- Reverse Lookup: IP → domain using PTR.

DNS Caching & Performance

- Caching Levels: Browser, OS, resolver, ISP.

- TTL (Time To Live): Controls cache freshness.

- Low TTL → quick updates (good for dynamic services).

- High TTL → fewer queries, better performance.

- Anycast Routing: DNS servers route queries to the nearest location.

- CDN Use: Cloudflare/Akamai leverage DNS caching for speed.

Security in DNS

- DNSSEC: Cryptographic signatures for authenticity, prevents tampering.

- DoH (DNS over HTTPS): Encrypts DNS queries inside HTTPS traffic.

- DoT (DNS over TLS): Encrypts DNS queries with TLS.

- Threats:

- DNS Spoofing → Fake responses redirect traffic.

- Cache Poisoning → Inject malicious DNS data.

- DDoS on DNS → Overwhelm resolvers/authoritative servers.

Real-World Failures

- Dyn DNS Attack (2016): DDoS using IoT devices took down Netflix, GitHub, Twitter.

- Azure Outage (2020): Misconfigured DNS update caused global service disruptions.

- GitHub (2018): Brief downtime due to incorrect DNS TTL values delaying failover.

These examples highlight why redundancy, monitoring, and correct TTLs matter.

Practical Considerations

- Performance: Use short TTL for dynamic services, long TTL for static domains.

- Redundancy: Always have multiple authoritative servers.

- Monitoring: Track query latency, error rates, cache hit ratios.

- Internal DNS: Used within service meshes (e.g., Istio, Envoy).

- Private DNS Zones: Offered in cloud providers (AWS, GCP) for secure internal resolution.

Troubleshooting DNS

- Tools:

dig www.example.com→ Check resolution path.nslookup→ Simple queries.whois→ Registry/ownership lookup.

- Common Issues:

- DNS propagation delays (TTL too long).

- Missing glue records for subdomains.

- Misconfigured MX records breaking email.

Interview Relevance

Typical FAANG-style question:

“Design a globally distributed DNS service for your product.”

Key points to cover:

- Use anycast for global distribution.

- Deploy redundant authoritative servers.

- Add DNSSEC for security.

- Cache responses aggressively with CDN support.

- Monitor latency and provide failover.

Conclusion

DNS is the invisible backbone of the internet. It connects users to services, distributes load, and underpins availability. For engineers and interviewees alike, mastering DNS means understanding caching, resolution, redundancy, and security.

Key takeaway: In design interviews, talk about global distribution, caching, and DNSSEC. In real systems, focus on redundancy, monitoring, and failover strategies.

Further Reading

- Computer Networking: A Top-Down Approach – Kurose & Ross

- RFC 1035 – Domain Names: Implementation and Specification

- Cloudflare Learning Center on DNS and DNSSEC

- Google & Akamai engineering blogs on DNS performance and security