How the Internet Works: From URL to Website

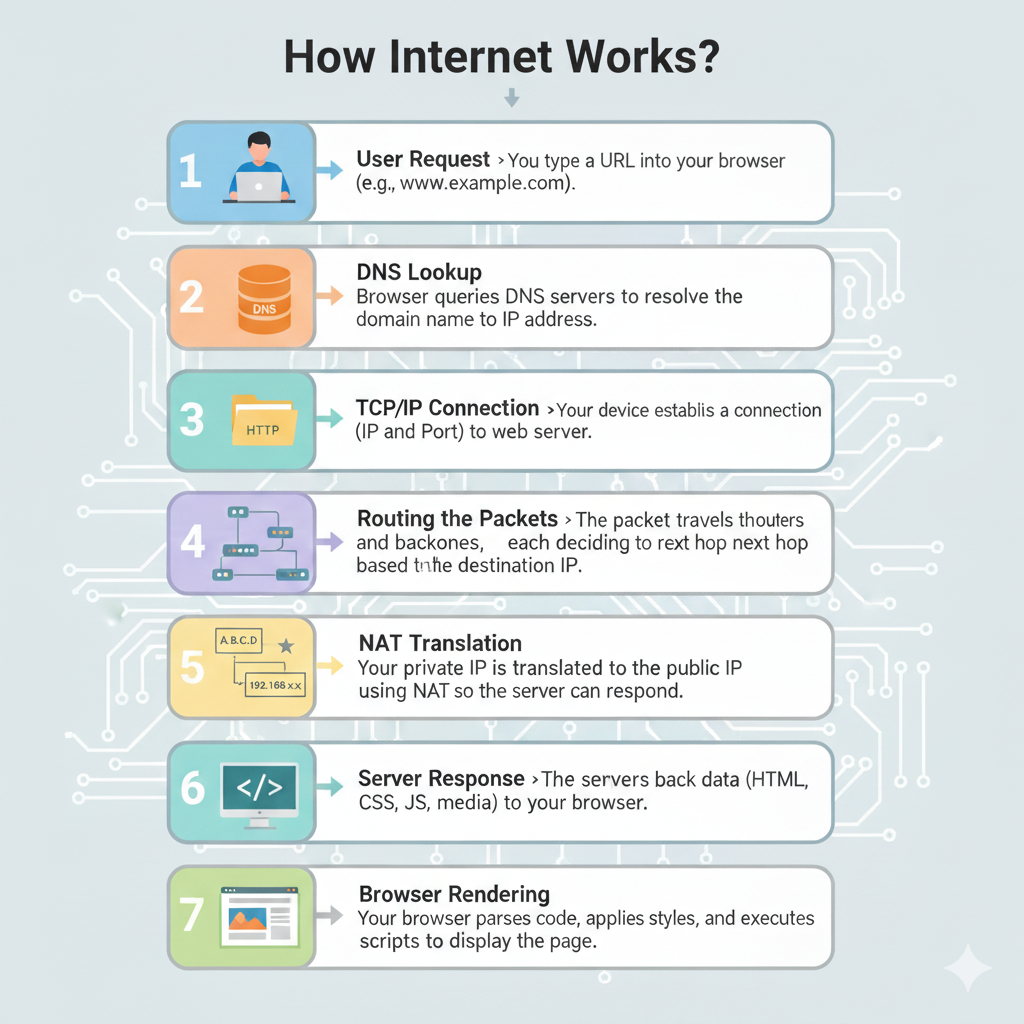

When you type www.example.com into your browser and hit enter, a fascinating chain of events unfolds in milliseconds.

This journey involves domain names, IP addresses, routers, and translation layers that allow billions of devices to communicate seamlessly.

Let’s follow the step-by-step journey of a web request — from the moment you hit Enter to the moment the web page appears on your screen.

1. The Journey of a Web Request

Step 1: You type a URL

You open Chrome, Firefox, or Safari and type:

www.example.comAt this point, your browser doesn’t know where "example.com" is located. It needs an IP address — the real numerical identifier of the server.

Step 2: DNS Lookup — Finding the Address

The browser first checks its local DNS cache to see if it already knows the IP.

If not, it asks a DNS resolver (usually provided by your ISP or Google DNS 8.8.8.8).

The resolver then:

- Asks the root DNS servers (who knows about

.comdomains?). - Queries the TLD servers (who knows about

example.com?). - Finally, queries the authoritative server for

example.com, which returns the IP address, e.g.93.184.216.34.

Now your browser knows where to send the request.

Step 3: IP & Ports — Preparing the Request

Your computer forms a packet addressed to the destination IP.

- IP address tells the network which machine.

- Port number tells the server which application (e.g., port 80 = HTTP, port 443 = HTTPS).

If it’s HTTPS, a TLS handshake will happen later to establish encryption.

Step 4: Routing the Packets

The packet leaves your device and travels through a series of routers:

- Your home router → your ISP’s router.

- ISP forwards it to a regional backbone.

- Large networks exchange packets using BGP (Border Gateway Protocol).

- Eventually, the packet reaches the server hosting

example.com.

Each router looks at the destination IP and decides the next hop, until it finds the right path.

Step 5: NAT — Sharing Limited Addresses

If you’re on IPv4, your home devices use private IPs (like 192.168.x.x).

Your router uses NAT (Network Address Translation) to replace your private IP with your ISP-assigned public IP, so the server can reply.

Without NAT, billions of devices couldn’t share the limited IPv4 space.

Step 6: The Server Responds

The server receives your request, processes it, and responds with:

- HTML → the structure of the page.

- CSS → the styling (colors, fonts, layout).

- JavaScript → interactive behavior.

- Images, videos, etc.

These files are split into packets and sent back over the same route (possibly via different paths, since the internet is redundant).

Step 7: Browser Renders the Page

Your browser now does the heavy lifting:

- Parse HTML → build the DOM tree.

- Download and apply CSS → create the render tree.

- Execute JavaScript → modify DOM and fetch extra resources (AJAX, APIs).

- Paint pixels on the screen → you finally see the web page.

This all happens in fractions of a second.

2. The Building Blocks (Glossary of Terms)

To recap, here are the technologies working behind the scenes:

- DNS (Domain Name System) → translates human-readable domains to IPs.

- IP Addressing → every device on the internet needs a unique identifier.

- IPv4 (32-bit, limited) vs IPv6 (128-bit, virtually unlimited).

- Routing → routers forward packets using routing tables and protocols like BGP.

- NAT (Network Address Translation) → lets private devices share a single public IP.

- TCP/UDP → transport protocols ensuring reliability (TCP) or speed (UDP).

- TLS/HTTPS → encrypts traffic between you and the server.

- Browser Rendering Engine → turns HTML, CSS, and JS into the web page you see.

3. Interview Tip

When asked “How does the internet work?”, always explain it as a story/journey:

- Browser → DNS → IP.

- Packet → Routing → NAT.

- Server → Response → Browser rendering.

Then highlight supporting concepts like IPv4 vs IPv6, BGP, and HTTPS for security.